CLIMATE ISSUE: Urban stormwater quality; Fluvial (riverine) flooding; Erosion; Ecological degradation | SECTOR: Landscape architecture, Stormwater management; Ecology | STAGE: Completed | TYPE OF ACTION: Green infrastructure; Nature-based solution; Ecological restoration | TYPE OF SETTING: Urban watershed; Brownfield; Urban park

Project Overview

Located along the Bow River in Calgary, Alberta, Dale Hodges Park represents a transformative restoration project that converts the former Klippert gravel pit extraction site into a public park and public artwork installation. A collaboration between O2 Planning and Design and Source2Source, with AECOM, Sans Façon, and the City of Calgary, the project uses sculpted landforms to integrate an innovative stormwater management system with habitat restoration and recreation, to restore the degraded riparian and aquatic habitats, treat stormwater runoff, and introduce new opportunities for public use while making vivid the movement of water through the system.

Location: Calgary, Alberta

Actors: O2 Planning & Design (landscape architecture and park design), AECOM with Source2Source (stormwater engineering, environmental design, and hydraulics), and Sans Façon for Watershed+ (public artists)

Funding Agency(s) / Programs: City of Calgary

Issue: Degraded ecological integrity of the former quarry; Stormwater quality entering Bow River

Action: A multi-stage biofiltration system, comprising both highly technical engineered stormwater infrastructure and ecological-based solutions, including wetland and riparian habitat and vegetation restoration.

Results: Ecological regeneration; Ecosystem-based flood protection; Hydrological restoration; Stormwater treatment; Public recreation and amenities

Lead: O2 Planning and Design and Source2Source

Project Background

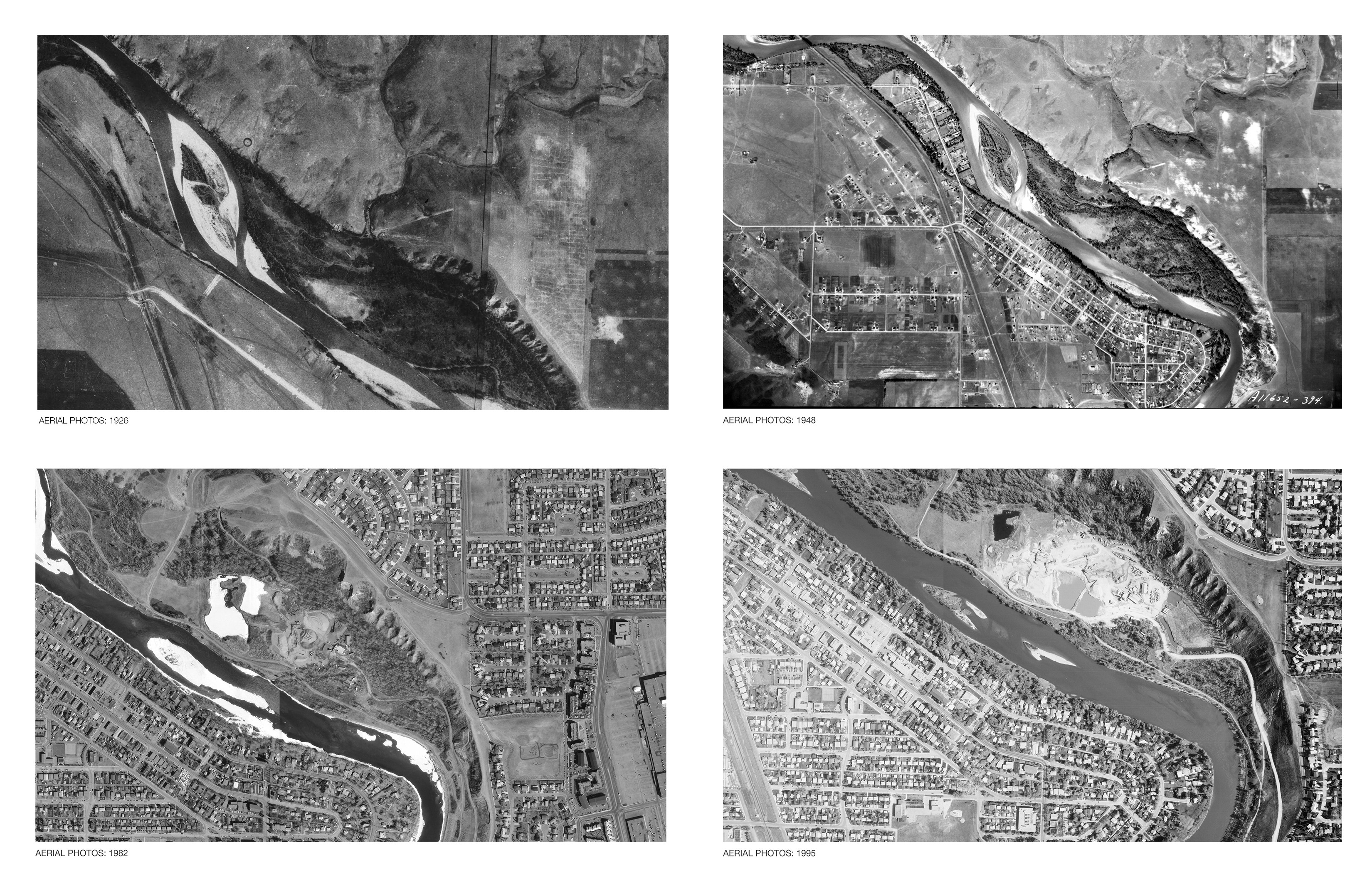

The conceptual groundwork for Dale Hodges Park traces back to the 1990s through collaborative discussions between the City of Calgary and the Province of Alberta, particularly concerning the impacts of urban stormwater catchment sites on the city's riverine environments. This period of negotiation resulted in a shift toward integrated and sustainable approaches aimed at mitigating the environmental impacts of urban development on rivers and creeks.

From these discussions, AMEC Engineering was commissioned in the early 2000’s to conduct a comprehensive study identifying potential stormwater improvement sites across the city, aimed at enhancing stormwater runoff quality and restoring critical ecology. Bernie Amell (landscape architect, Source2Source) was a primary co-author of this study. The study identified Bowmont Park (later renamed Dale Hodges Park) as a high-priority site.

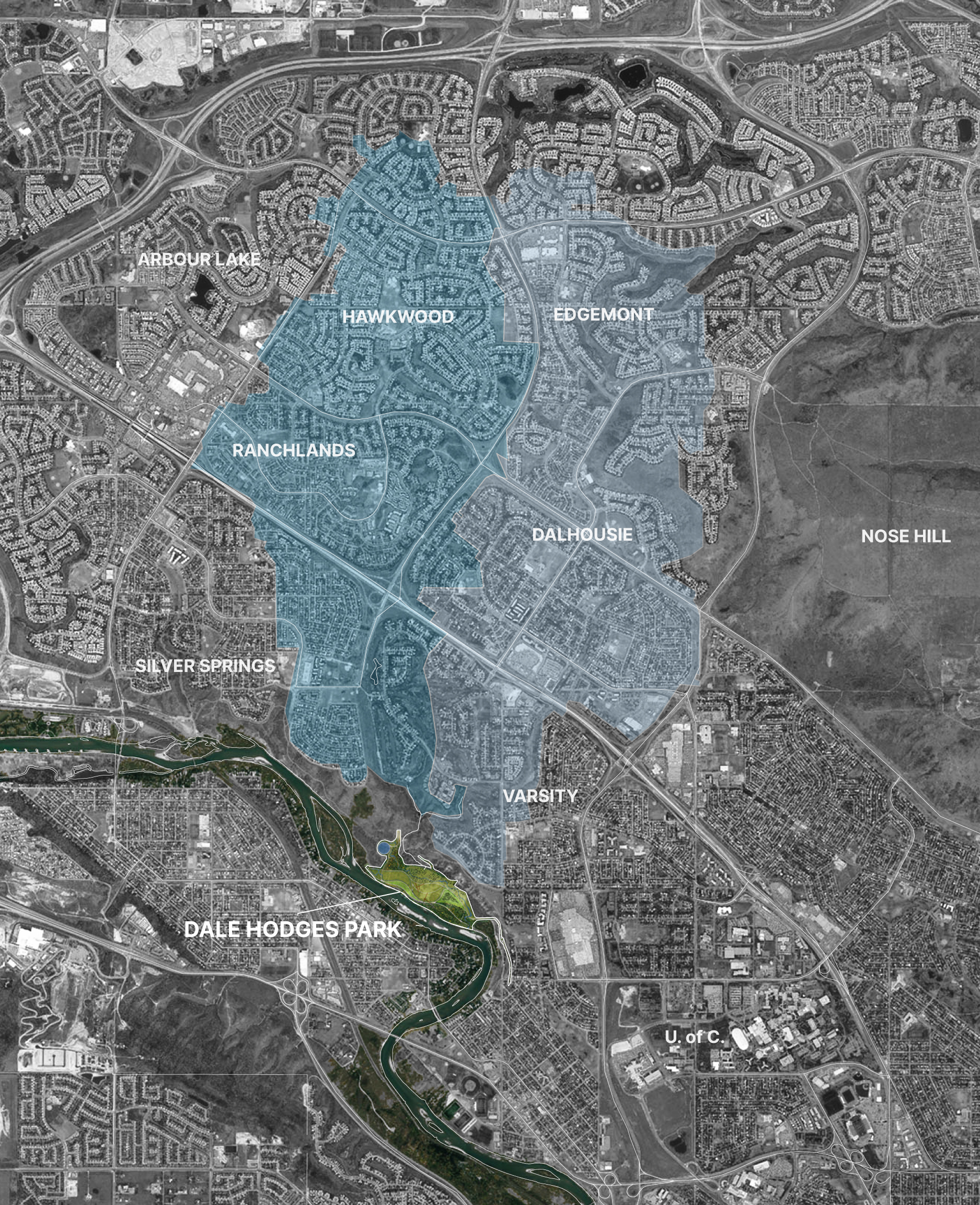

In 2010, the City of Calgary acquired the former Klippert gravel pit, located along the northern bank of the Bow River within Bowmont Park. At the time, Calgary was experiencing rapid growth and development pressure. The acquisition of these lands presented an opportunity for the treatment of stormwater from an intensively urbanized catchment of over 1800 hectares before entering the Bow River, which would not only see the transformation of the ecosystem into a functional habitat for wildlife, but also the enhancement of community amenities and access to nature.

Understanding and Assessing Impacts

The site surrounding Dale Hodges Park sits at the outfall location of a large underground stormwater system discharging into the Bow River upstream of a bull trout spawning area. This presented environmental and hydrological opportunities, but also infrastructural complexities to the project.

The riverine, riparian and valley escarpment ecosystems of the Bow River Valley are among the most important natural features in Calgary. The Bow River is a cold, clear mountain river, and has a unique trout-oriented stream ecology. Before the area became a gravel pit in the mid-20th century, it historically contained a natural stream channel. However, warming and pollution led to reduced oxygen levels and nutrient enrichment, which significantly impacted the trout stream and ecological health.

To address water quality concerns and the ecological degradation of the site, the principal objectives of the project were the treatment of stormwater before entering the Bow River, and the restoration of the ecosystem. This project presented an opportunity to regenerate the native habitats, restore the historical hydrological system, reconnect people to the river through recreation and park amenities, and to demonstrate municipal commitments to environmental sustainability.

Use of Climate Information in Decision-Making

A series of studies and analysis of existing conditions, including site hydrology, vegetation, habitat quality, current uses and infrastructure, and utilities and stormwater, were conducted.

At the center of the project is the stormwater management system, designed to adapt to a range of flow conditions, from frequent low-flow events to extreme flooding. This flexibility reflects climate projections for Southern Alberta, which indicate that both the frequency and intensity of storm events will increase. At the downstream area, the design integrates an erosion-resistant spillway that functions as a safety valve during high-water or backflow events. This feature enhances the ecological function and protects both the stormwater structure and the surrounding habitat from damage.

The stormwater treatment system is organized into nine treatment cells, each designed with unique soil conditions, plant communities, and hydrological characteristics. This diversity of ecologies enhances water quality and supports the natural regeneration of habitat across deep and shallow marsh zones. Likewise, the varied hydrologic conditions and plant interactions foster biodiversity and provide habitat for a wide range of species.

The flow of water within the park begins in the upstream residential communities where runoff travels through pipes before daylighting in the park, passing through built structures and streams into a series of polishing marshes, wet meadows, riparian areas and a 900 meter long restored stream. At the upper reaches of the constructed stream, stormwater enters the Nautilus Pond which removes a high proportion of sediments and floating contaminants that would otherwise overwhelm more sensitive components of the system downstream.

Flows up to 5 cubic metres per second (cm/s), are then directed through the riparian forest and into the constructed stream that runs along the wetland complex, where it receives further treatment for finer sediments, dissolved nutrients and other contaminants. Infrequent major flows, in excess of 5 cm/s up to ~20 cm/s, bypass the treatment wetland and receive treatment by the constructed stream and riparian habitats in biomimicry of beneficial flooding events. This deliberate reconnection of hydrology restores the forest’s natural flood cycle by allowing silt deposition and nutrient cycling to occur, creating a productive riparian ecosystem.

A dual-pipe system is used to accommodate both small and large storm events, where smaller pipes manage routine flows but carry higher overall pollutant loads, and larger pipes are activated during major storm events. Upper “Source Walls” (a term coined by the artists to describe the installation) are engaged during extreme rainfall by releasing rainwater prior to entering the Nautilus Pond or allowing water overflow to return to the stream without disrupting the wetland system. These walls also serve as public art making, allowing visitors to witness the fluctuations of the water levels during different storm events.

Identifying Actions

The project was highly collaborative, comprising a large multidisciplinary team to develop the design, ultimately pursuing a concept that highlights the journey of stormwater through the intentional integration of water engineering, public art, landscape architecture and ecological design. The project was jointly led by the City's Water Resources and Parks departments with the multidisciplinary design team working collaboratively to achieve multiple departmental goals and objectives.

Art played a significant role in the design of Dale Hodges Park. At the time of development, the City required that a portion of all major infrastructure budgets be dedicated to public art. This led to artists being embedded in the design team at the very beginning of the project to help the City establish an overall vision for the project. In addition, public engagement workshops hosted as part of the East Bowmont Natural Environment Park Design Development Plan process (2012 to 2014) also directed the park’s design. This collaboration introduced creative opportunities to interpret and reveal the story of stormwater.

In alignment with Alberta’s Stormwater Management Guidelines (1999), the project’s stormwater system was designed to achieve at least 80% removal of total suspended solids (TSS) under normal operating conditions before water is released back into waterbodies. The standard is set to ensure that the stormwater infrastructure significantly improves the water quality and protects the ecosystems downstream. The other ecological objectives of the design required a significantly higher sediment removal performance.

From a technical perspective, the objective was to develop a multi-stage biofiltration system, culminating in an infiltration zone and an ecologically enhanced stream. Conceptual decisions aimed to facilitate a visceral experience for park visitors by making the stormwater treatment process, and subsequently the ecological restoration process, apparent at each treatment stage as the water travels to the Bow River. Drawing inspiration from meander scrolls (a unique riparian phenomenon that reveals a river’s evolving path) these forms support stormwater treatment functions and shape the visual and experiential identity as the organizing elements. Using ecosystem-based strategies of sculpted wetlands, wet meadows, and marshes to slow, clean, and store urban stormwater, the landforms and natural habitats are contrasted with the park’s network of pathways and boardwalks.

Summary of design intentions:

- Restore land impacted by previous gravel pit operations;

- Treat urban stormwater;

- Restore ecological habitats and biodiversity; and

- Provide recreation opportunities for visitors.

Implementation

The implementation of the East Bowmont Development Plan occurred over four phases, with the initial phase focused on the construction of the stormwater management facilities and the areas adjacent to the stormwater features. The subsequent phases concentrated on habitat restoration, trail and pathway development, as well as the amenities and facilities that are not directly associated with the stormwater quality management area.

The project integrated ecosystem-based filtration, habitat restoration, and hydrological management throughout the design. Emergent vegetation, shallow groundwater inputs in the riparian forest, and the restored creek channel work together to support fish and other wildlife while treating urban runoff.

The stormwater system is designed to intentionally mimic natural processes, including seasonal flooding and sedimentation, to maintain ecosystem function and resilience under variable climate conditions. As a restored seasonal creek, the outlet stream discharges into a trout-rearing habitat, supporting adaptation during times of high flooding. During the implementation process, early signs of success included the return of trout to the tail end of the system, demonstrating biodiversity recovery and the restoration of the clear, low-nutrient aquatic ecosystem.

Outcomes and Monitoring

The project was completed in the fall of 2018, opening officially as Dale Hodges Park in June 2019. Once a contaminated gravel pit, the site has now been remediated and transformed into a functional, natural space that not only treats stormwater, but facilitates biodiversity recovery and climate resilience, while using landform art as a high-performance public space. The project has received numerous local, national, and international awards for its innovative approaches to integrating stormwater management, public art, and public spaces along the banks of the Bow River.

The multidisciplinary and highly integrated approach taken by the City of Calgary was critical to the project’s success, bringing engineers, landscape architects and ecologists and public artists together to collaboratively envision the park, transcending disciplinary boundaries and creating a complexity of experiences. The strong political and municipal leadership was significant, and helped to ensure that economic pressures did not compromise the project’s vision, providing the long-term perspective and support necessary to coordinate and deliver the project’s goals.

One of the project’s biggest champions was former Calgary city councillor Dale Hodges, for whom the park was later named in recognition of his contributions. The success of the project illustrates the value of orchestrating complex, cross-disciplinary teams, showcasing the importance of visionary planning, strong governance, and collaboration as essential for the successful delivery of large-scale urban ecological infrastructure projects.

The project employed a systems-based approach to restoring the landscape to fit within its novel ecological and cultural context, inherently advancing long-term biodiversity recovery. Emergent vegetation zones provide natural stormwater filtrations, enhance habitat, and contribute to the ecosystem’s climate resilience.

Biodiversity, particularly the presence of trout and numerous native bird species, continues to serve as key indicators of the project’s ecological performance. The anticipated performance for sediment capture has been exceeded, and the performance of the Nautilus Pond continues to be closely observed to ensure the system functions as intended: sediment accumulates in an outer ring, and sequestering floating debris is periodically removed.

Highlights of the Landscape Architect

The Dale Hodges Park Project illustrates a dual approach to landscape architecture, combining the highly technical, bioengineering and ecological science aspects with creative design input. The site’s complexity required a multidisciplinary team, including landscape architects with expertise in different aspects of the project, to achieve both the water management system and ecological restoration goals within the broader framework of urban park development.

The project exemplifies the intersections of science, art, and ecology in landscape architecture. It positions the landscape architect uniquely alongside engineers, ecological scientists and artists, where the design landscape architect served as a translator of the technical requirements presented by the engineers into spatial form, while also incorporating the vision of the artists. The result was a concept that not only functions ecologically and technically, but is also visually engaging and provides a rich visitor experience.

Next Steps

During the COVID-19 pandemic, park visitation increased significantly, highlighting the value of the project as both a wildlife refuge and a destination for people to connect with nature in the city. Currently, efforts are underway to enhance visitor experience with additional educational interpretive signage.

While there currently exists no dedicated funding for long-term monitoring of the park’s ecological and stormwater performance, the project’s effectiveness has been demonstrated through other indicators. These lessons, in addition to the collection of performance data when possible, can be used to inform future restoration and urban infrastructure initiatives. As municipalities increasingly pursue nature-based solutions, funding for long-term monitoring is essential. A record of the performance over time that can be shared with the next generation of designers, ecologists, and city-builders is necessary to demonstrate the lasting value of ecological infrastructure.

Resources

- City of Calgary (2014) - East Bowmont Natural Environment Park Design Development Plan.

- City of Calgary - Protecting the Bow River - Storm water design objectives.

- City of Calgary - Parks - Dale Hodges Park

- O2Design - Dale Hodges Park Project Portfolio

- Green Communities - Case Studies - Dale Hodges Park

This case study was prepared and authored by Sabrina Careri (Design Communications) on behalf of the CSLA.

It forms part of the landADAPT Case Study Series, an educational resource and advocacy tool developed by the CSLA with the support of Natural Resources Canada’s Climate Change Adaptation Program.