Quick Facts

Name

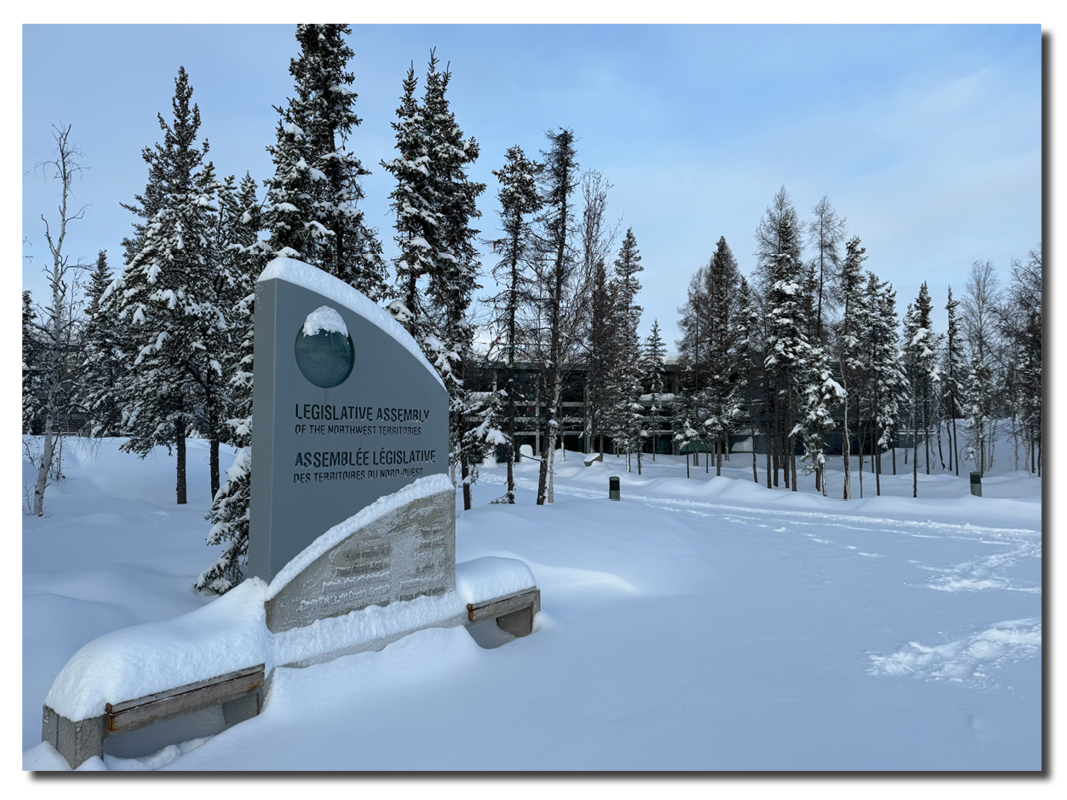

Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly

Type of Landscape

City precinct

Rough subarctic terrain of rock/ boreal forest/ bog in Canada’s extreme north

Location

Yellowknife, NWT

62°27'34.362''N ; 114°22'55.046''N

Stewards

Government of the Northwest Territories

Legacy

Enhanced Planning/ Design Strategies for the extreme north

Raised Sensitivity to ecological integrity of the north

Pioneered new techniques for fragile northern sites and provoked collaboration

Introduction![]()

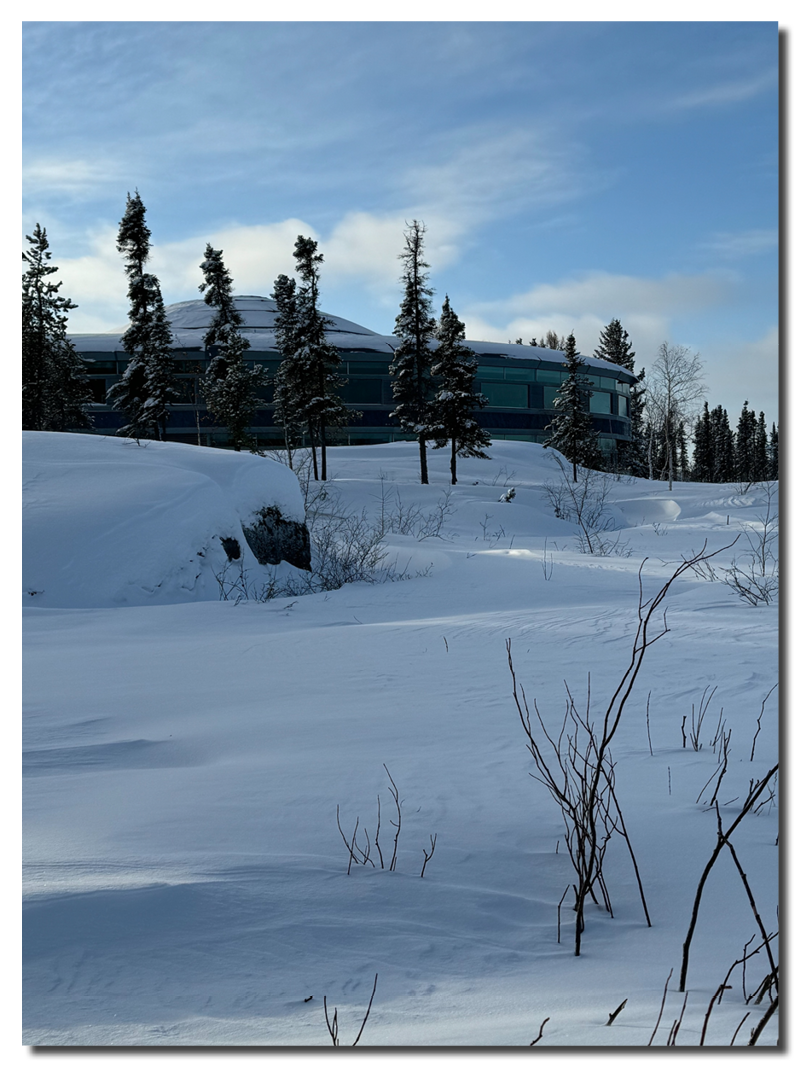

The shallow dome of the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly building rises above the rough rock outcrops, the black spruce and tamarack on the shores of Yellowknife’s Frame Lake. The gentle curves of the sculpted building elegantly punctuate the rugged terrain. Its circular meeting hall is a tangible reminder of the nature of this government. Here, consensus is the goal.

The Assembly, the legislature’s first permanent home, belongs to the people of the NWT. It is just a short walk from the centre of NWT’s capital city of Yellowknife.

For centuries, this dramatic northern landscape of boreal forest, taiga and ancient peat bog lay largely undisturbed. Yet by 1993, the district had become the symbolic and official home of the NWT government’s major institutions.

The remarkable transformation began with a group of planners committed to shaping a municipal assembly with its natural setting largely intact. The Architects of Pin Matthews (Yellowknife) and Matsuzaki/ Wright (Vancouver) joined forces with renowned landscape architect Cornelia Oberlander.

Oberlander had long been recognized for her revolutionary landscapes which endure, and indeed thrive, in highly complex conditions. In Yellowknife, she tackled enormous odds. Here, the land’s rugged appearance belies its fragility. The bog had been damaged by fire; the subarctic ecosystems were notoriously difficult to restore. Suitable greenhouses and native plant materials were scarce to non-existent.

In response, Oberlander opted to use the project site itself to generate plant life, collecting and salvaging native vegetation, then shuttling stock to Vancouver greenhouses 2000 km away. The plantings prospered, and the expansive flatlands, together with the natural composition of rock, forest and lake, became “a masterpiece of environmental design,” says historian Ron Williams. When the sweeping winter snows disappear, the landscape flourishes with birds and waterfowl, and a rich palette of local color graces the lands.

Decades after its inception, the Assembly stands testament to the sensitive handling of fragile landscapes of the extreme north in a period of political, cultural and climatic change.

Restoring an ancient bog

Above all else, Cornelia Oberlander was determined to honor the NWT’s tundra and taiga landscape, and the expansive boreal peatlands so critical to their health.

These ancient and highly sensitive bog lands had immediately drawn the team’s attention. The bog’s flat expanse would become a poignant transitional space, separating the rugged setting of the new Assembly from the more pragmatic street life of the city.

Technically, this would prove more of a challenge than anyone had predicted. Historian Professor Susan Herrington tells the story in her landmark biography, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander: Making the Modern Landscape.

“When Oberlander arrived at the site … she discovered that portions of the peat bog had been destroyed by fire,” writes Herrington. “Although peat bogs are extremely difficult to reestablish, their valuable contribution to water and air quality as well as the unique habitat they afford made their restoration … critical.” (p.189)

“In response, Oberlander devised what she called “the cookie tray technique.” Instead of bulldozing the bog for the … roadway entrance, she instructed the contractor to use the earthmoving equipment like a giant spatula. Similar to lifting cookies off a tray, the plant material in the bog was scooped up and transferred to the disturbed areas of the existing bog.” (p.190)

Peat mats removed whole during construction were transferred wherever they were needed. By salvaging the bog material, writes Herrington, “Oberlander saved a valuable organic material that may have been in gestation for 1000s of years.” (p.191)

“True Children of the North”: Planting beyond the bog

Cloudberry, rose hips, mountain cranberry, vaccinium, and kinnikinnick. In the 1990s, these native jewels of Oberlander’s plant palette simply were not available in Yellowknife nurseries.

For Cornelia Oberlander, the solution lay in her own mantra, “Plant what you see.”

Professor Susan Herrington explains, in Cornelia Hahn Oberlander: Making the Modern Landscape, her biography of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander. Oberlander began to think about the project site itself as a generator for its own plant life. With horticulturist Bruce McTavish, she collected seeds, clippings, and tissue cultures to build a healthy stockpile of existing native vegetation.

Since in those years, greenhouse propagation was not possible in NWT, Oberlander decided to transport the collection to Vancouver greenhouses. She returned with the young vegetation when spring began.

On site, she renewed the site’s construction-damaged areas by using a technique she called “invisible mending,” a term borrowed from sewing. Again, she transplanted mats of plants and soil to damaged locations, interspersing them with sedges and cloudberry. The genetically-related plantings, as she expected (hoped), prospered. They were, says historian Ron Williams, “true children of the north.”

Everywhere, the site bears witness to Oberlander’s determination to walk lightly on the land. Instead of adding paved paths, the team installed boardwalks that float above the bog and taiga terrain, protecting the valuable plants below and allowing animals to pass beneath. The elevated walkways connect the site to a 4.5 mile trail that encircles the lake.

Oberlander’s highly effective work provoked a growing sensitivity among site planners and designers working in the Far North. Like Oberlander, they began to prioritize the ecological integrity of the northlands, and began to listen to locals, people who had previously been ignored. Oberlander pioneered a new-found spirit of collaboration, and developed techniques which have enhanced the relationships between new structures in the North, the fragile landscapes of these remote regions, and Indigenous peoples.

The Cultural Landscapes Legacy Collection highlights the achievements that have made a lasting impact within the field of landscape architecture and on communities across Canada.